El Niño, the climate phenomenon characterized by warmer-than-average sea surface temperatures across the equatorial central and eastern Pacific Ocean, has far-reaching impacts on weather patterns across the globe.

El Niño events can last for several months up to a year or more and typically peak in the winter months of the Northern Hemisphere, so we’re likely to see El Niño conditions continue to strengthen over the coming months, said Alyssa Atwood, an assistant professor in Florida State University’s Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Science, part of the College of Arts and Sciences.

During an El Niño event, warm ocean surface waters in the central and eastern Pacific Ocean alter atmospheric circulation patterns and affect weather systems worldwide.

El Niño events are the warm phase of a cyclic climate phenomenon known as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, generated in the tropical Pacific through interactions between the atmosphere and ocean. These events typically occur every 2-7 years and can have severe impacts both within and far outside the tropical Pacific. In different regions, strong El Niño-Southern Oscillation events can cause drought, flooding, changes in tropical cyclone activity, crop failures, disease outbreak and the collapse of marine ecosystems.

At the moment, sea surface temperatures are 3°C (5.4°F) warmer than average in parts of the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean and the latest predictions from the Climate Prediction Center at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration suggest that El Niño conditions will persist through next spring, peaking as a strong El Niño event around November to January, Atwood said. The last time a strong El Niño event occurred was in 2015-16 and it was associated with widespread impacts that affected millions of people around the globe.

Here’s what’s anticipated during continuing El Niño conditions, according to Atwood:

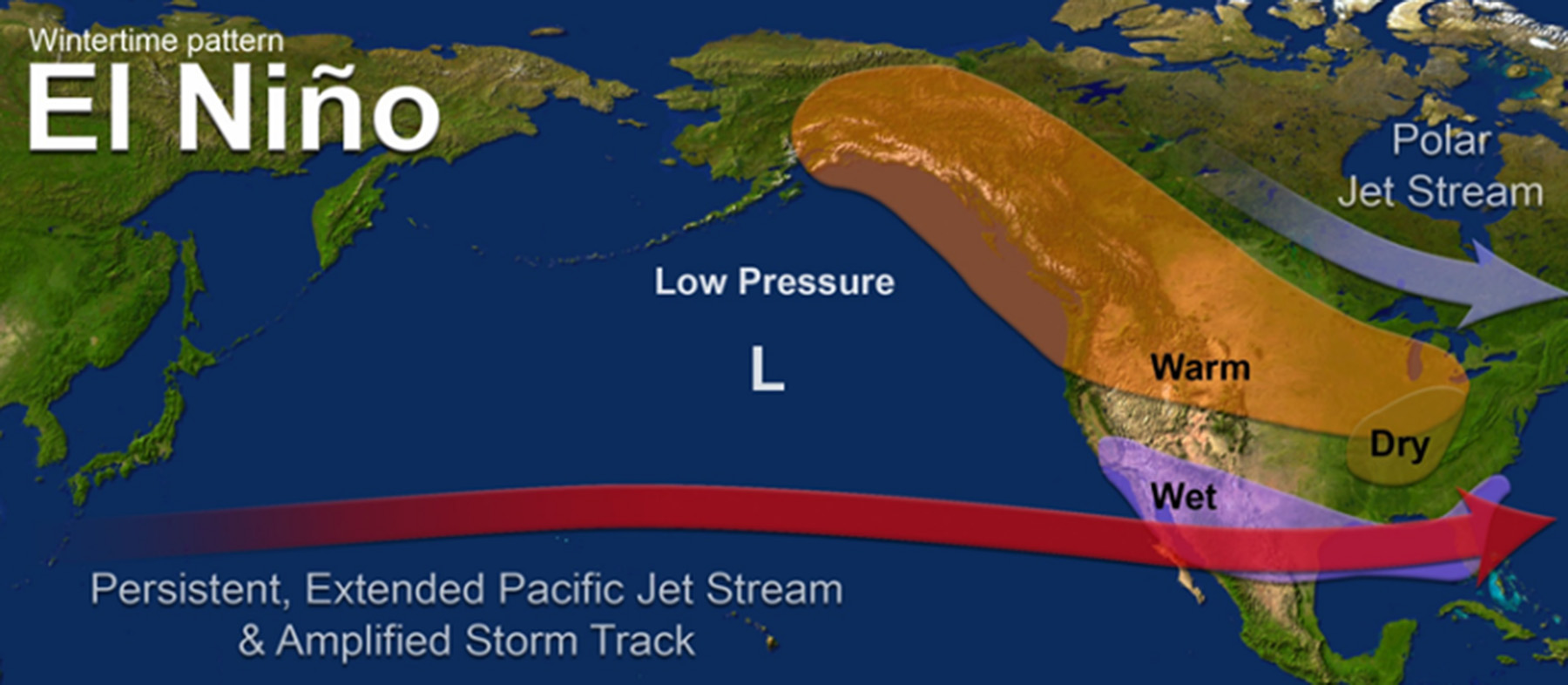

Warmer or wetter winters: One of El Niño’s primary effects is on winter weather conditions in certain regions. In North America, a continuing El Niño tends to bring above-average temperatures to the northern United States and Canada. This can lead to reduced snowfall and milder winter conditions, which may be welcome news for those who dislike shoveling snow but can be a disappointment for winter sports enthusiasts and the snow sports industry.

In parts of the southern United States, including the Southwest and the Gulf Coast, El Niño often leads to wetter conditions from October to March due to an enhanced subtropical jet in the atmosphere that steers storm tracks farther south than usual. This can result in higher-than-average rainfall in the region, which may alleviate drought conditions but can also bring the risk of flooding.

Stormy spring: As El Niño events persist into the spring months, their influence on weather continues. Spring can bring an increased likelihood of severe weather events such as heavy rainfall, thunderstorms and tornadoes in certain regions. The southern United States is vulnerable to these extreme weather events during El Niño years.

Global implications: El Niño has a global footprint. In South America, countries like Peru and Ecuador often experience heavy rains and flooding during El Niño events. This has impacts on agriculture and infrastructure. Conversely, parts of Australia and Southeast Asia may face drought conditions, affecting crops and water resources.

In Asia, the monsoon season can also be disrupted, leading to irregular rainfall patterns and potential challenges for agriculture, water management and infrastructure planning. Similarly, African nations may experience altered rainfall patterns with potential consequences for food security and water resources.

Alyssa Atwood

Assistant professor, Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Science, aatwood@fsu.edu (850) 644-1116

Alyssa Atwood is available to speak to the media about El Niño and its potential impacts. Atwood has taught courses in oceanography and meteorology since joining FSU in 2019. She earned dual bachelor’s degrees in physics and atmospheric science from the University of California, Berkeley, and both a master’s degree and doctorate in oceanography from the University of Washington. Her research focuses on combining records of past tropical climate variability with modern data, theory and climate models.

“Other El Niño impacts I see firsthand in my research are the devastating marine impacts that can accompany strong El Niño events under changes in sea surface temperatures and ocean upwelling patterns. The strong El Niño event of 2015-16 killed over 85% of the corals in Kiritimati Island, where I conducted research in the central equatorial Pacific due to ocean temperatures that were over 2°C above average for many months. The reef was only just starting to recover before this latest El Niño event hit. Troublingly, these extreme events are now happening on top of rising background temperatures in the ocean, and together, they threaten the future of coral reefs as we know them today.”